by Nadiah Mohajir

With the increased visibility of the #MeToo movement, everyone is having conversations about sexual violence. But unfortunately, not everyone has the tools or understanding to make these conversations productive. Whether these conversations take place on social media, in person, or in interdisciplinary professional spaces such as coalitions or taskforces, there is often a disconnect between those who are showing up as allies, and the people they are trying to stand in solidarity with. This can result in obvious tensions, but also difficult conversations that can result in multiple harms, leaving those who identify as allies feeling confused and rejected, offended at the notion that their allyship was not enough or that it fell short.

To be clear, the common understanding of an ally is someone who wants to show up, or stand in solidarity with someone who does not have the same lived experience or identity as them. So, for example, a nonblack person standing in solidarity with a Black person; a man standing in solidarity with a woman against misogyny; a cisgender, heterosexual person standing in solidarity with LGBTQ folks against homophobia and transphobia; nonMuslims standing with Muslims; a member of the community wanting to support survivors of sexual assault.

As I continue to work in the reproductive justice and anti-sexual assault advocacy movements and raise awareness on these issues in Muslim communities, the exclamation “But I’m an ally!” is something I hear almost on a daily basis. In this present day of social media activism, respectability and identity politics, and sensationalized hot button issues, many are quick to jump on the opportunity of being an ally, but are not fully prepared to do the hard and messy work of true allyship. Some understand identifying as an ally absolves one of criticism; that one’s desire to be an ally is in and of itself enough: however, showing up is just the first, and often, the easiest step. One of the biggest lessons I have learned when working with directly impacted people is that being an ally not only requires deep, deep humility, but also a nuanced understanding of microaggressions, the various manifestations of short-term and long-term trauma, and the acceptance that being in a movement comprised of directly impacted folks and allies will inevitably result in multiple harms. Working through those multiple harms, understanding one’s privileges and power in each situation, and centering those that are directly impacted is what ultimately can lead to true allyship. As such, allyship is not:

- simply standing in solidarity with another or attending a protest or rally.

- just a formula, or a list of actions one can do to show and prove they are allies.

- the number of “fill in the blank” friends you have.

- how many Black Lives Matter rallies or Pride parades you’ve been to.

Rather, it is acts of solidarity that allies show a marginalized person or community, that can be received (or otherwise rejected). Simply performing those acts of solidarity are not enough. It is showing up when needed, not when it is convenient. Allies do not get to decide if they are allies: rather, it is up to those who allies are trying to stand in solidarity with to determine whether they accept them as allies. An ally is committed to stand in solidarity, even if they feel uncomfortable or criticized by the directly impacted.

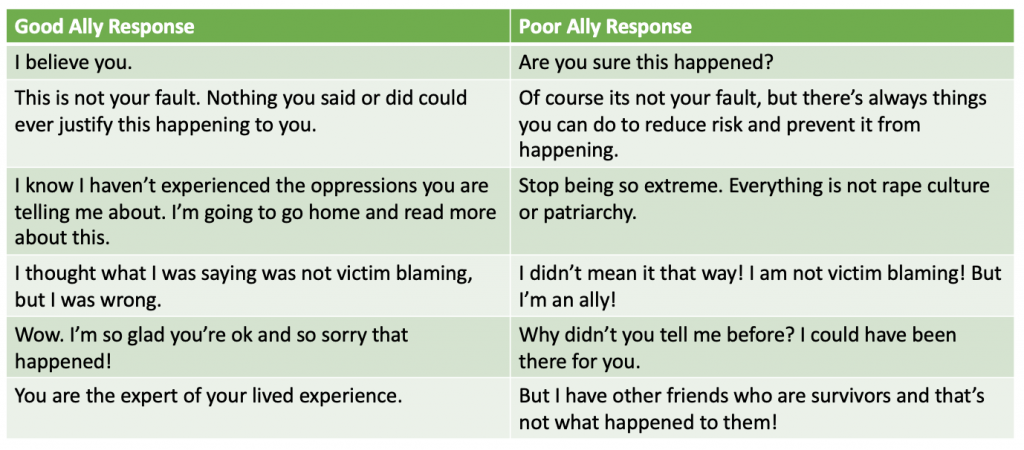

So when I am asked how an ally can show up for survivors, here are a few tips. While this list is specific to allies of sexual assault survivors, note that these tips can work for allies who want to show up in other movements, such as the racial justice movement, LGBTQ inclusion movement, etc.

One: An ally understands that those most directly impacted are the experts. An ally must center survivors and their stories and listen to them. Continuing to belabor their own point, and insist they are right not only tells the survivor they are not listening, but also can contribute to further re-traumatizing and triggering the survivor and others who may be silently witnessing the conversation. Moreover, I’ve often seen allies using their own (unrelated) professional expertise and lens to continue to be argumentative with those they are trying to be in solidarity with. This is not to say that allies and survivors and their advocates cannot engage in healthy debate about issues, but rather that the ally has an open mind: they must consider that they may not have that same understanding because of the inherent reality that they do not – and may never – have that same lived experience. It is inherently that lived experience that makes the survivor more an expert than the ally and it is that experience and understanding that should be given priority in any conversation. Moreover, it is not the responsibility for those who are directly impacted to change hearts and minds; it is the responsibility of the allies to do that work, which inevitably will be uncomfortable and challenging.

Two: An ally assesses their own privilege. Having privilege is in and of itself not a bad thing or something one needs to be defensive about. What one does with their privilege, though, can have a significant impact. An ally is in the constant practice of being aware of the privileges they bring to every space, and understands that certain privileges – particularly those unearned (gender, color of skin, identity) can create unequal power dynamics between them and those that are directly impacted. These unequal power dynamics can make it much easier for allies to silence, discredit, or exploit survivors and their advocates, as allies generally have more resources available to them – including unearned systemic privileges such as those granted on basis of sex, race, and sexual orientation. Moreover, assessing one’s privilege also includes acknowledging the reality that oppression for marginalized folks does not stop. For example, survivors will repeatedly interact with trauma and rape culture. Women will always face systemic patriarchy, people of color will always experience racism. Therefore, it is important for allies to realize that stepping away or not engaging with a certain oppression is also a privilege that those they are supporting are not afforded. Moreover, to reiterate the point from above, an ally steps up when needed, not when it fits conveniently into their life.

Three: An ally apologizes when they are wrong. An ally can demonstrate commitment and solidarity to standing with survivors by apologizing for any harm – even and especially when it is unintentional – that was created by their words or actions. Even if they believe they too, were harmed in the process. In other situations, I’ve seen allies not only refuse to apologize, but demand an apology for how they experienced the interaction, insisting that their feelings were hurt. An ideal apology includes self-reflection on what happened, and does not double down on how they were right. A good apology often exercises humility and integrity and models the phrase “I thought I knew but I was wrong*.” Most recently, Chance the Rapper modeled this type of humble apology shortly after the release of the R Kelly documentary series. Finally, an ally makes a commitment to accountability: to act differently moving forward and learn from the mistakes of them harm they committed.

Four: An ally remains committed to continued education and difficult conversations. It is not the responsibility of survivors to educate their allies. Allies should work to gain a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the issues and challenges facing survivors by reading, studying, taking workshops and trainings. Allies also work to understand the issues from a systems lens, how systems can enable oppressions to continue, and how allyship can often recreate systems of oppression if not done right. They work to understand how trauma manifests, and how multiply marginalized people experience microaggressions and the impact of multi-generational oppression. This of course does not happen overnight. It requires a long-term commitment to ongoing educational opportunities.

Five: An ally reduces the emotional labor that directly impacted folks have to do everyday. Before responding an ally should ask themselves, “Am I making this about my feelings?” By asking questions like “How come you never told me before?” or “I’m an ally, I’m not a racist – that’s offensive,” the ally has shifted the attention from the survivor’s feelings to their own. Moreover, an ally can work to reduce the emotional labor that survivors have to do by having conversations with their own people. This can include being supportive so a survivor doesn’t have to be in the constant practice of explaining themselves, the situation, or their feelings. This also includes shutting down victim blaming, rape culture, inappropriate jokes, when they happen in their presence.

As the fight for a more inclusive and safer world continues to gain more visibility, allies can play an important role in advancing the cause of those they are standing in solidarity with. However, with this role comes the need for allies to also bring with them a continuous commitment to humility, integrity, and accountability. Allies will inevitably make mistakes, and that is okay. The challenge is to learn from those mistakes so as to not recreate systems of oppression.

* I am grateful to the Move to End Violence Racial Equity and Liberation team for teaching me about this area of learning.