analysis by HEART + Justice for Muslims Collective

Every couple of months, our communities erupt with new allegations of gender-based violence (GBV). Many times, these allegations involve respected and revered community leaders – often male – who are accused of horrifying acts of physical, sexual, and/or spiritual abuse. This is followed by a cycle of events, with this violence occurring at every level of society:

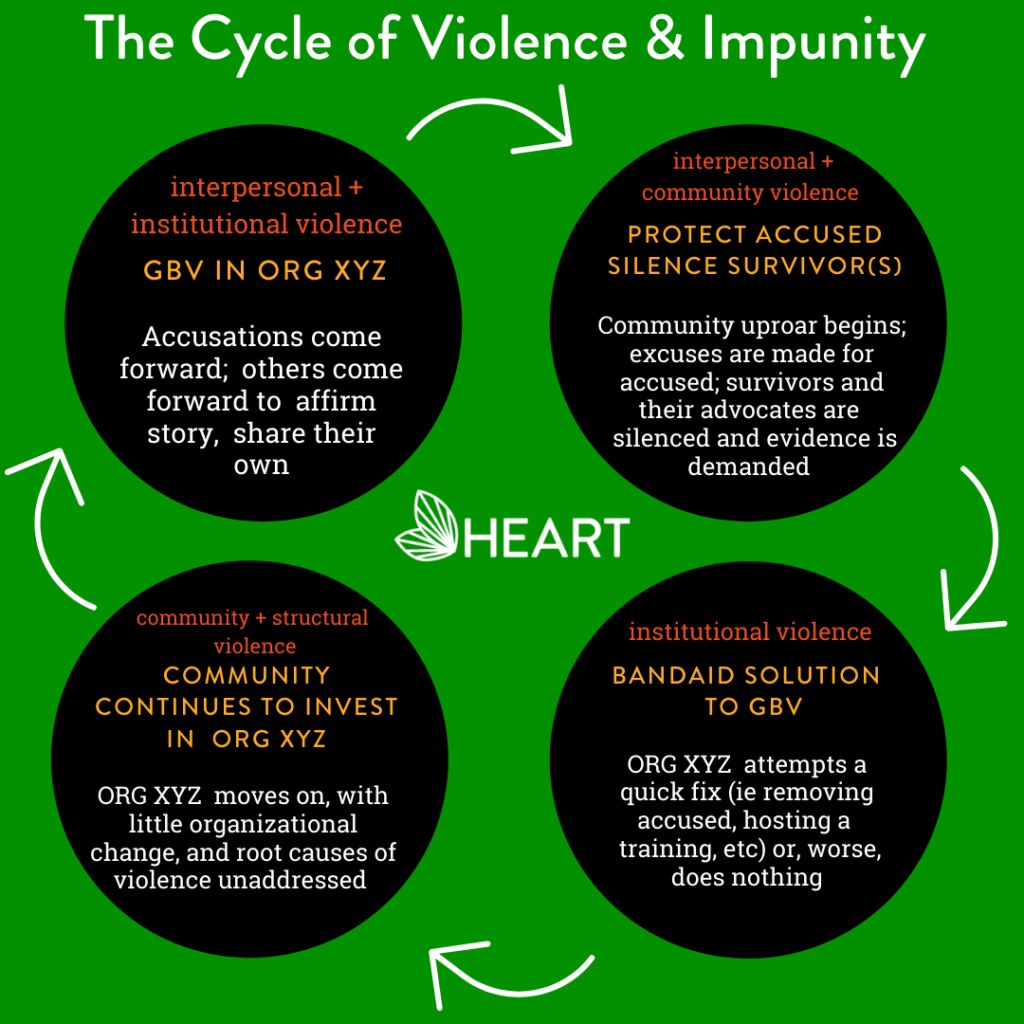

- Allegations of harm are revealed when a survivor(s) comes forward; others come forward to affirm the story, and share their own stories of harm, often at the hands of the same leader or institution (interpersonal + institutional violence).

- Community uproar begins: excuses are made for the accused, followed by a statement of defense made by the accused. Survivors and their advocates are silenced and evidence is demanded (community violence).

- The organization/community attempts a quick fix (ie removing the accused, hosting a training, etc) or, worse, does nothing and given there is no such a thing as being neutral in these situations, sides with the accused (institutional violence)

- A narrative is also created that the accused is the actual victim and is being targeted because of who they are or the power/money/fame they have.

- The culture of harm in the organization/community is not challenged and the quick fix does little to address the root causes of the violence.

- The community continues to donate to and supports the organization, and provides platforms to the accused. (community + structural violence)

- Follow up with the impacted survivors is left to a small group of advocates, who are further vilified and accused of destroying communities and families. (structural + community violence)

- This individual incident also further harms survivors who are less likely to come forward due to the lack of community support and active hostility and victim-blaming of survivors.

And the cycle continues, a few months later, sometimes with different players (other times with the same players) but the same textbook series of events. Hence we end up living in a cycle of impunity where survivors are consistently disposed of and excluded, and systems of power and privilege are preserved. This cycle is illustrated below, and shows the relationship between interpersonal violence, community violence, institutional violence, and structural violence.

As we consider this pattern, an important question to ask ourselves is: how are we, as individuals, as communities, and as institutions, contributing to this cycle of violence? At which point do we, as individuals, communities, and institutions, have the power to disrupt this cycle? Many of us struggle with the discomfort of interrogating these questions because it inevitably brings a hard truth to the surface: that we all, in some way, are contributing to this cycle of gender-based violence. However, the first step to disrupting the cycle of violence at every level is to reckon with this very reality.

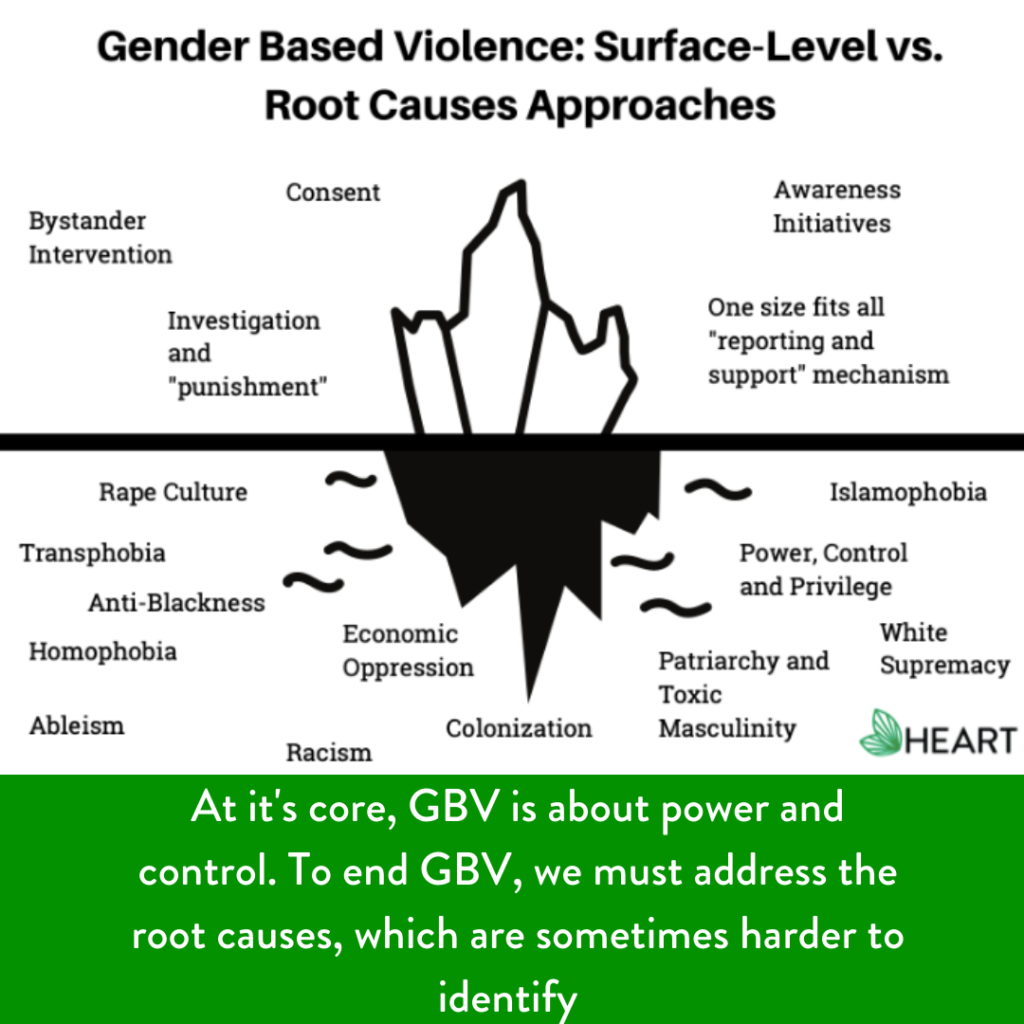

Over the years, we have had no shortage of organizations, initiatives, and activists calling attention to this cycle, raising awareness on various types of gender-based violence (GBV), and calling for more accountability, justice, and a proactive commitment to prevention in our institutions. And yet, this cycle of violence occurs over and over again, and the ever present question rises to the surface: Why haven’t we seen a decrease in the prevalence of GBV despite all the good work happening?

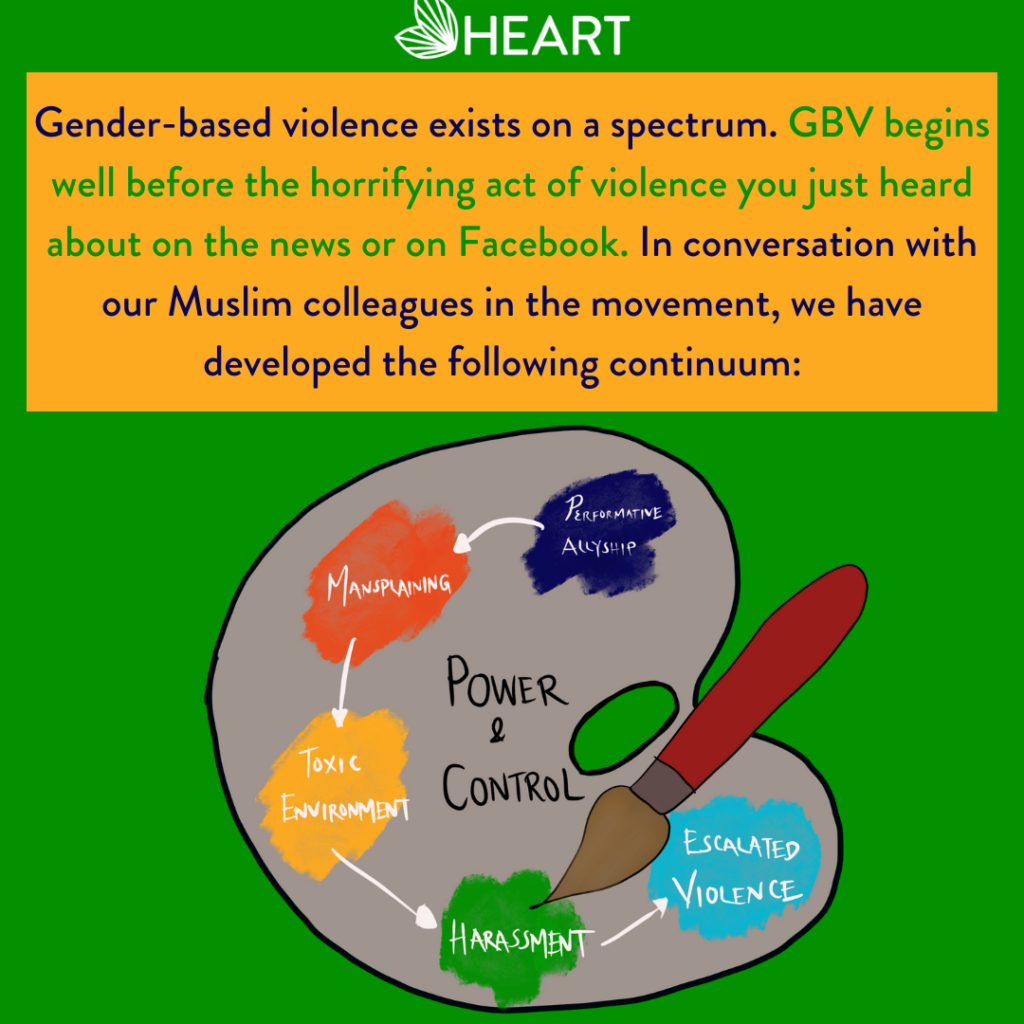

The answer to this question requires an understanding that gender-based violence exists on a spectrum. GBV in our organizations doesn’t begin with the horrifying act of violence you just heard about on the news or on facebook. Rather, it begins well before that. We identify this as spectrum of gender based harm in Muslim spaces. This spectrum of behaviors isn’t necessarily linear and exclusive – they can be overlapping, reinforce, and exist in the same plane together.

We can identify behaviors, actions, and instances where these parts of the spectrum show up in our Muslim communities, organizations, and families.

- It can be seen with the ever-present pay inequities coupled with toxic work environments, and an unhealthy work-life balance.

- The gender and racial discrimination.

- The tokenization of marginalized identities, while concentrating power in the hands of people with privileged identities.

- The silencing (or firing) of staff that try to speak up when they feel they are being mistreated or challenge authority.

- The silencing of former employees by asking them to sign NDAs when they leave.

- The boards that are informed of inequities in their organization and choose not to do anything about it.

- It begins with the reality that our communities continue to invest in organizations that perpetuate harm and under-resource those working to dismantle those systems.

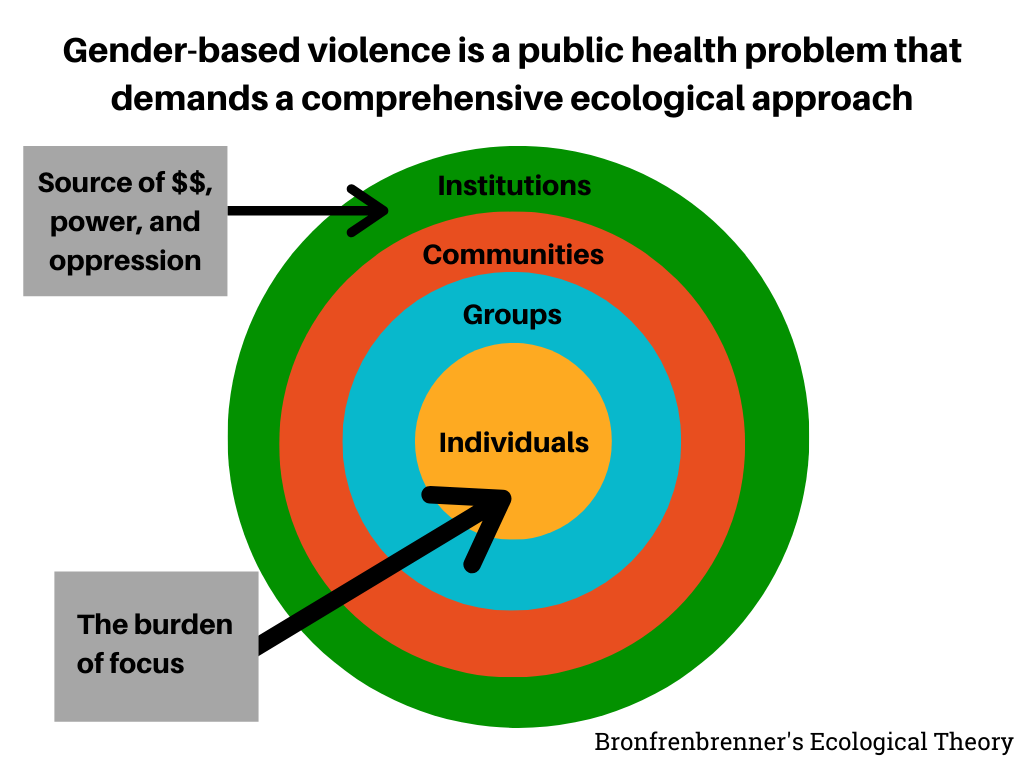

As such, it is critical to approach GBV using a comprehensive ecological approach that shifts the burden of focus of prevention efforts from the individual (ie bystander education, crisis intervention, general education) to the institutional and structural level: which more often than not, is where the source of money, power, and oppression lies.

This shift requires thinking about what institutional and structural accountability looks like:

- What policies (structural and institutional) need to be implemented to reduce the burden of reporting on survivors?

- How does power need to be redistributed so that the most impacted are not tokenized, or worse, further marginalized, but truly uplifted, seen, and heard?

- How can boards and institutional leadership engage in accountability practices that actively work to reduce harm when and as it is happening instead of as an afterthought. This requires relationship building with staff and not just executive leadership.

- How do fundraising and philanthropy practices preserve certain systems of power?

- How can institutions and leadership use their large platforms for public education campaigns that address some of the root causes of gender-based violence such as racism, white supremacy, toxic masculinity, and rape culture?

For far too long, our communities have been investing in structural violence. While we do not have the power to disrupt GBV at every level, or even change every institution, we can do our part in holding our institutions accountable. Accountability can take many forms. Consider the following:

- Withholding donations, and other types of support, like inviting those accused of doing harm to give keynotes, sit on panels, etc

- Asking for leadership change, and interrogating how leadership is identified and selected. By what criteria? By what ethical standards are they held to?

- Challenging organizations to think about their workplace cultures. This can include considering the racial and gender makeup of their leadership, staff, and board, and their practices around inclusion. Who is allowed into their spaces? Who experiences a barrier to entry into their spaces? Who holds decision making power? Is power concentrated in the hands of a few, or distributed throughout the organization? How are they working to build more equitable workplaces?

Our faith has a strong tradition of upholding justice and protecting the most marginalized. It is imperative our institutions are organized in such a way that models this tradition. We must ensure that leaders and organizations across Muslim communities aren’t further replicating the violence they are trying to address in their workplaces, toward their colleagues, and their families. It’s important that our leaders are in integrity and consistently practice what they preach. Movements have often failed, in part, due to the tolerance of patriarchy, misogyny, and violence by male leaders. What is destroying our communities is the lack of support for those who are marginalized and the upholding and preservation of structures, norms, and leadership that actively harm. Gender-based violence cannot be seen as a lesser issue of importance to address, but rather should be seen as integral to the fight for our collective rights and liberation.

Leave a Reply